|

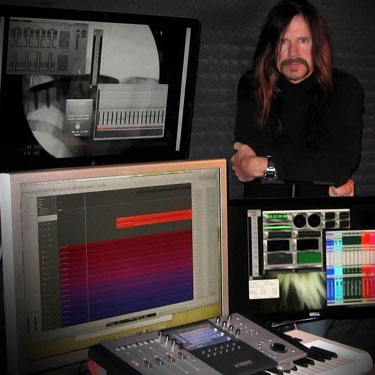

Jack Hale Jack Hale

NASHVILLE, TN: Jack Hale does it all, and he does it all well. An instrumentalist, a musician, a composer, an engineer, and a producer, Hale has enjoyed a storybook career.

Inspired by the successful and meaningful lives of his father and uncle, musicians both, Hale took up the trumpet at thirteen and quickly obtained a virtuosic proficiency that earned him a place in the music department at the University of Memphis. Hale befriended John Fry and Joe Hardy, and they gave him the keys to Ardent Studio to use as he wished in the off hours. Meanwhile, Hale was selected as the trumpet player in the Memphis Horns and had a hit single to his credit at the tender age of twenty (on Al Green's "Full Of Fire"). While touring as a trumpet player with Johnny Cash, Cash recognized Hale's genius and hired him to be his musical director. Hale held the position during the last decade of Cash's life, which was one of the most prolific periods in The Man in Black's storied life.

The ebullient Hale is good natured and humble, recognizing that his list of accomplishments (which could go on and on and on – he's worked with everyone!) is in equal measure good fortune and dedicated professionalism. These days, he spends most of his time producing and engineering high-profile artists and shepherding the talented musicians who, if the winds of fate are fair, will blossom to become high-profile artists. Hale has come to rely on the three cornerstones of Metric Halo's product line to speed his workflow and guarantee the impact of his projects. "I rely on Metric Halo's ULN-8 interface, ChannelStrip plug-in, and SpectraFoo sound analysis software for everything I do," he said. "In fact, even though I have a refrigerator rack loaded with the best outboard hardware you can imagine, I would still feel like I had every necessary tool at my disposal if you stripped me of everything but a computer and my Metric Halo hardware and software."

Hale started engineering in the halcyon days when "landlines" were called "phones" and "analog recording" was called, simply, "recording." He was oriented to the almost-tangible sounds he got using SSL, Neve and Harrison consoles and the rack of drool-worthy gear he amassed from the proceeds of his early production gigs (allowed because the musician gigs still paid the rent and put food on the table). When hard disc digital recording entered the scene, Hale tried the available plug-ins at the time and found them, in contrast to the analog sounds with which he was acquainted, soulless. "I could see the advantages of hard disc recording," he said. "And it was hard, after so many years of compromising productions for the lack of available tracks, to resist blossoming sessions up to fifty tracks or more. Sure, I could rely on my outboard gear to process a few of those tracks, but not fifty. I really needed a plug-in that sounded great."

Metric Halo's ChannelStrip was that great sounding plug-in. "Metric Halo offered it as a free trial, so I tried it," Hale said. "I couldn't believe how great it sounded. The compression was responsive and the EQ had the authenticity of a good hardware unit." Hale used ChannelStrip on countless projects, and it is still the workhorse in his mixing environment, be it Digital Performer, Logic, or Pro Tools. Nevertheless, Hale put ChannelStrip to its most powerful use during his last sessions with Johnny Cash. "I had used ChannelStrip on a song I produced for Johnny called "The Man In White." He had a cold or something at the time and I was able to get the sound of his vocal back rather easily with the Metric Halo gear. I remembered that when I recorded his vocal on "Missionary Man" as Johnny was suffering the effects of a degenerative disease, as his voice was not all that it had been. I used ChannelStrip to sculpt his voice back into form matching timbre between different passes to make a really good comp."

When it came time to get a portable interface, Hale asked a knowledgeable friend for a recommendation. "He said, 'if you want deadly-accurate preamps and converters, you need a Metric Halo ULN-8,'" Hale reported. "I tried one and found he was absolutely right. I was blown away by the clarity of everything I was hearing. It was like someone switched on the 'clear' filter!" Hale purchased three ULN-8s, two that could stay at his home studio (Hale House Productions) and one that could travel with him in a shoulder bag.

Although initially intimidated, Hale has come to depend, in the truest sense of the word, on Metric Halo's MIO Console (he also reports that today, that barrier to entry has been lifted by Metric Halo's user-friendly improvements). MIO Console allows users to route signal between all the inputs and outputs of a Metric Halo hardware interface and the inputs and outputs of an editing or recording DAW (e.g. Pro Tools). Moreover, it offers its own recording functionality and, where applicable, controls Metric Halo's sophisticated onboard DSP. "My workflow is literally ten times faster with MIO Console than, heaven forbid, without it," Hale said. "I build channels, perform zero-latency monitoring, and customize routing with it, among many other things. It's ideal when you have a larger input configuration for a particular song and can store/recall the MIO console with every parameter you created or adjusted, every time you return to work on the song. Same goes for mixing. I would hate to do without MIO Console."

Hale also runs Metric Halo's SpectraFoo software at all times and constantly flips to it to verify that a recording or mix is problem-free. "When I took the time to internalize SpectraFoo's array of – at first glance – geeky tools, the world changed for me," Hale said. "In addition to being able to align my speakers and shoot my room, I use it on a daily basis to diagnose problems, or to catch problems before they become audible." For example, Hale and the musicians he works with use a lot of vintage gear, which, in addition to its obvious charms, comes with some inherent instabilities. During tracking Hale takes snapshots or movies of SpectraFoo's tools (like phase correlation maps, spectrographs, and the like) and then uses those snapshots as points of reference on subsequent days. "It's really easy to see when a tube is failing – way before you can hear it," he said. "Or I can tell if an apparently missing frequency is due to equalization (and thus fixable) or a phase problem (and thus unfixable). Spotting problems like that early on can save a costly day's work." |